Designing with & for ML/AI

How to work with anticipatory & probabilistic experiences

As per some reports from HBR1 , WSJ2 and others, something like 50-80% of machine learning projects end up in failure. As per research by technical leaders like Eric Siegel3 it is often more because of reasons like business objectives & alignment, definition & measurement of success, etc. Design is equipped to ease this process like with other types of technologies and help explore and envision the future, de-risk it, help define success and then help to bring it to reality in its most sustainable, viable, and of course, desirable form.

Designing for and with these technologies does still use all the fundamentals of designing good experiences, but designing with ML/AI is non-deterministic, and can benefit from considering the specific strengths of these technologies while guiding or guard-railing the experience against their weak points or vulnerabilities, by design.

Here are 5 key things to remember when designing for & with these technologies.

Don’t skip the discovery phase

Familiarize with the data first

Know when ML or AI & why

Understanding the models

Exploring & testing patterns

1. Don’t skip the discovery phase

This is the part that doesn’t change from more conventional product development. However, often ML/AI problems can suffer from fuzziness because, by definition, these are usually problems that are too complex for humans to capture. It also does not help that this field is moving and evolving fast, and new developments are unlocking new capabilities.

What problem is ML/AI best suited for?

It’s important to avoid falling prey to throwing a business or user problem directly into the AI box and hoping it will solve it for you. And even if you started with the technology to explore what kinds of new capabilities you can unlock for your product or domain, these technologies can be expensive and time consuming to get to production.

It helps to begin with either a capability of the technology or the strategic or user problem. In both cases, you want to get to a narrower definition of which part of a scenario is best tackled with these technologies and what the likely gains or risks to the outcome are. Design prototyping is very helpful with exploring this up front, ensuring that we are simulating the outcome scenarios, anticipating user needs, and weighing the risks that can help scope out the definitions of success for the technical team to assess.

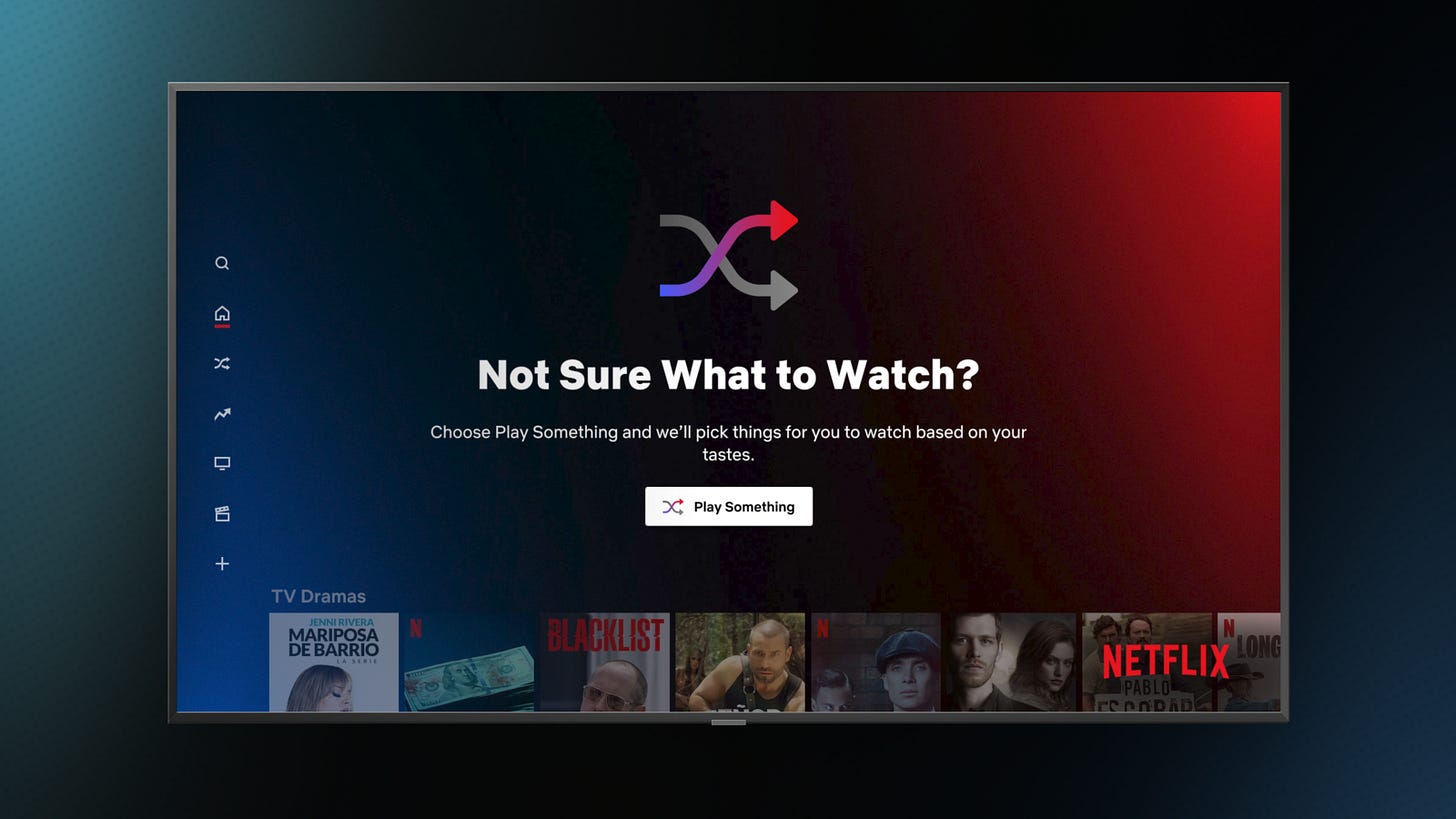

For eg. Netflix’s “Surprise me” feature wanted to solve for arguably the biggest user pain points– choice paralysis. On release, though, it didn’t perform. This is because predicting a few items from a large multi-genre catalog to suit a user’s subjective & random mood at any a particular moment is not a good prediction problem, even with a lot of recent data (often missing for large chunks of your users). Predictably, Netflix said that “..subscribers usually resort to browsing for videos in certain categories, such as horror or romantic comedies, rather than bet on the shuffle mode surfacing enticing content.”

In this case, the feature leveraged ML but without considering the human context, it ended up increasing the effort (and disappointment!) for users, losing their trust in the process.

How well is the desired output achievable with ML/AI?

Based on how high or low-stakes the problem is, what output does the tech need to deliver, and how well would it able to do so? Just because you “can”, doesn’t mean you always should solve something with ML/AI. For eg. u

When we know the type of problem or the data itself may lower reliability, we can consider using design to explore ways to help improve accuracy or hande failure situations. As a user mentioned about the Netflix Suprise me feature–

“Surprise me” would be fine if it was relocated specifically within a particular genre. I could get down with that, but spamming the whole catalog is absolutely chaotic.

– Random user on the internet

2. Familiarize with the data first

At this stage, I’m assuming the tech team has some confidence that this is a technically feasible problem, so work with them to understand the data. In projects using ML/AI, you are often not building the functionality itself as much as building a learning mechanism to enable some functionality. The currency of this learning is the data, and so in effect, the data and its quality is what determines the quality of your functionality. So it’s very helpful to begin by understanding which data outputs we need, how well does it create these outputs, or how well does it need to, and what are the resultant needs that the experience must cater to. Working cross-functionally to understand this and make it explicit can help create the shared understanding to get more creative in the next stages of this process.

What are possible outcomes based on the data?

Furthermore, even if there is conviction in using the technology, thinking through potential scenarios of faulty correlations and bias, inevitable accuracy failures, learning feedback loops, etc helps to surface ethical risks early, define direction or decisions, and explore certain user experience questions.

3. Know which technologies and why

There are certain use-cases where one is better than the other. It’s important to consider their strengths and risks as we consider these use-cases. For eg. If I had to help a creative professional create a great deck, I can solve it by recommending a few out of 1000 of great templates with full control & snappy ways to edit. But perhaps because the customer is a busy business leader, the feature that provides value is turning their written doc into an entire presentation instantly– content curated from the doc, add appropriate images, auto layout & theming. I’d then need to power it with genAI.

Machine Learning

What we’re calling machine learning here, is simpler predictive or classification models. These are great when you want to predict something based on your training data.

When there are too many choices or inputs/outputs, i.e., the rules are hard to define

When the relationships in the data are unknown, i.e., the problem is difficult to scope

When the steps towards an ideal end state is unknown

When the gains are better than simple heuristics but it’s still more efficient than resource intensive GenAI

When it might not be a good idea:

Accuracy needs to be a 100% or training data is messy or biased

Users need full transparency and/or control

People do not desire, or cannot trust, the automation

Generative AI

GenAI is just a bunch of technologies (eg. deep learning and large language models like GPTs) that can enable complex tasks by generating new data from the training data. They’re great when you need–

Open ended synthesis– of context, sentiment or argumentation

Summarizing, or selecting from, a large amount of content

Generation of content in, & interpreting between, modalities like text, images, video, audio, code, etc

Interpreting unseen patterns (eg. slang) based on previously learnt patterns

Creative and low-stakes tasks or when hallucinations (ouputs by models that can seem plausible, but are incorrect or flawed) can be detected or corrected via human-in-the-loop

When not to consider it–

When precise real-time data is needed eg. inventory checks

When the data permissions are missing or ambiguous

When the task is high-stakes, needs reliability & hallucinations are too risky

When it’s simply…too expensive for tiny benefit

Hope this gave you a more intuitive way to think about these problems before we dive into exploring them in design patterns!

(Points 4 & 5 to be continued in Part 2….)

https://hbr.org/2023/11/keep-your-ai-projects-on-track

https://www.wsj.com/articles/ai-project-failure-rates-near-50-but-it-doesnt-have-to-be-that-way-say-experts-11596810601

https://www.datacamp.com/podcast/why-ml-projects-fail-and-how-to-ensure-success-with-eric-siegel-founder-of-machine-learning-week